Well over 6,000 mills, water or animal powered, were documented in William the Conqueror’s Domesday survey of England in 1086 and at least 425 of these existed in Wiltshire; the majority were probably in use by the late Anglo-Saxon period of the 9th and 10th centuries. On average, it’s reckoned that one mill served around 50 households and Compton [Bassett] had a recorded population of 53 households at Domesday. The Norman feudal system dictated that only the lord of the estate could possess a mill, and by 1228 tithes from two mills were held by Compton Bassett manor. A duty, called a mill soke, was levied on tenants who took their grain to the mill with the toll being five per cent or more and given as grain to the estate. In return, the landowner paid for the mill building. Tenants had no choice but to take their grain there as no other mills, even handmills were allowed in the manor. The situation sometimes led to conflict with the miller who was often a victim of mistrust. A miller was brought to court before the lord of Compton Bassett manor in 1529, accused of overcharging. Medieval diet for poorer rural communities comprised porridges and thick cereal soups, flat-baked cakes and small loaves, all made using various types of cereal grain, commonly rye with barley, oats or beans. These were often supplemented with cheese, eggs or sausages.

Documentary Evidence

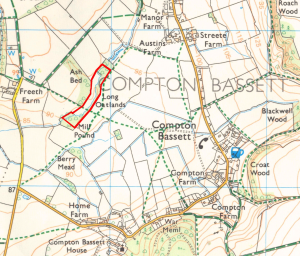

The Domesday survey also informs us that three estates existed in Contone (the Latinised name for Compton), each owning a third share of two mills; they were water-powered and almost certainly used for grinding corn. One mill was on the Abberd Brook about 400m south-east of Freeth farm, while the second was probably much further along the stream near Calne, where a mill known as Kew Lane Mill existed, yet still in land that was held by Compton estate then; this site is not appraised here.

Mills were a valuable economic resource and gave important information for King William I to be able to assess taxation. Reference to a fishpond is mentioned in a charter c.1233–1241, in which Philip de Cumberwell granted Gilbert Basset one acre of land beside a stream called ‘Penbrok’ to enlarge his fishpond. In 1321, when Compton Estate and 14 others held by Hugh Despenser the Elder were seized by the Crown, Compton House and many dwellings in the village were burnt in an act of retribution by the Earl of Hereford and followers. There was wholesale pillaging and it is noted that fishponds on estates held by the Despenser family were destroyed, although the Compton manor is not specifically mentioned. A further reference to a fishpond occurred in 1342, detailing a ‘hamme’ of meadow lying at the head of five acres of land at the lord’s fishpond, belonging to the lord of Compton Cumberwell manor (though it was probably in joint ownership with Compton Bassett manor). The use of the word ‘hamme’ is interesting because of its frequent association with water; it often described land that was hemmed in by water or land in a river-bed.

The large head of dammed water that was needed from this small water course for the mill also offered an opportunity to stock the pond with fish; eels, bream, carp and pike were among fish popular on the medieval dinner table, although very much a status food which few in a rural community could afford.

Three field plots in the 1839 Tithe Survey (Numbers 219, 222 & 250 on the map) and situated on the brook, or Penbrok as it was known then, are all called ‘Fisher’. It’s a clear reference not only to large ponds stocked with fish, but primarily they served as a head of water for the mill. The natural flow of the stream was inadequate and so the mill wheel would have been powered by gravitational force from the large volume of water stored in the pond. Its flow could then be regulated as and when millworking took place. Woodland at the western end of the site is still known as Mill Pound (252).

There is now no trace of the mill building on the Abberd Brook but earthworks for a dam and mill race can still be seen quite clearly. In fact two dams are there, one being 340 metres upstream of the other and it seems that an original pond, serving as a head of water to power a mill, was enlarged around 1240 by the construction of a second dam downstream to make a greater head of water. This was made possible by Philip de Cumberwell granting Gilbert Basset one acre of land beside a stream then called ‘Penbrok’. It also presented an opportunity to stock the now large millpond with fish, enhancing the resource greatly. It became popular on the medieval dinner table to eat fish such as eel, bream, carp and pike, although it was very much a status food which few in a rural community could afford.

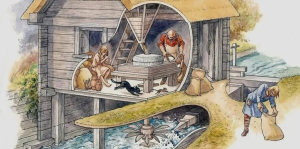

Watermills were commonplace in England by the later 1st millennium AD and various types have been discovered from archaeological excavation. The mass and depth of water available from the Abberd Brook made it best suited to a small-scale operation. An example of this starts with water from the pond entering the mill-race via a sluice gate, into an inclined funnel which directed water under pressure onto the side of a horizontal paddle wheel. This was connected by a spindle to the upper millstone. This upper stone could be adjusted so that the gap between stones controlled the fineness of the meal output. Lack of any rubble found at the site suggests the mill building was probably constructed with timber.

1994 Field Survey

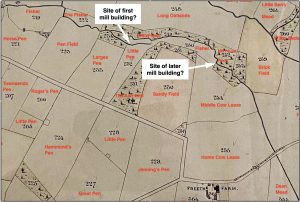

An earthwork survey of the mill pond site was carried out in 1994 by Christopher Currie. The scale of landscaping work undertaken to attract and retain the inflowing water courses can still be appreciated today. An 85m long by 3m high dam downstream (Dam 1) remains an impressive earthwork despite some erosion, and silting on the upstream side. On its western flank was once the site of a mill building of which there is now no trace. 340 metres north-east and upstream, is a much eroded smaller dam (Dam 2); this is the possible site for another mill. Both dams are aligned cross-valley and display evidence of a 90-degree inturn downstream on their western valley side for the course of a mill race, sluice gate and mill building. It is not possible to say if the dams and former mills are contemporaneous; following the survey a section was cut through the smaller north-eastern Dam 2 and was found to consist of sand and clay. Episodes of repair and consolidation were identified but no dating evidence was obtained. Nevertheless, it is noticeable that the smaller Dam 2 earthwork is more degraded than Dam 1 and so could be older.

A further pond (not included in Currie’s survey) almost certainly existed on the northern side of Dam 2, (Field number 219) again given the apposite name of ‘Fisher’ in the 1839 tithe map. Consequently, if the two ponds upstream of each dam were contemporaneous, was it possible there was sufficient power for two mills working in tandem? This must remain open to question. An alternative is also conceivable; corn milling may have continued at one site while the other was converted to fulling cloth (see later on). A more likely scenario for the chronology of earthworks along the Abberd Brook could well have begun upstream with the smaller Dam 2 and its fishpond. A mill may also have been situated here as there appears to be the vestige of a mill-race at the north-west end of the dam. It was subsequently abandoned, probably following the building of a second dam 340 metres downstream to harness a greater volume of water for increased mill production, and to provide better resilience against water shortage. This second phase may tie in with the grant of land given to Gilbert Basset around 1240 to enlarge the fish pond on the ‘Penbrok’. It seems unlikely that a reverse chronology could have occurred, as building a later site upstream of the first would have run the risk of compromising the effectiveness of a mill downstream.

Fulling Mills

Later on, milling operations changed to fulling, probably between the 14th and 15th centuries. Fulling is the process in woollen clothmaking that increases its thickness and density while cleansing the cloth of impurities. After a few hours in a fulling trough containing an alkaline solution (clay and urine were often used), the woven cloth was beaten and wrung dry. This procedure was repeated and then hot soapy water was used to help get rid of the natural oil and grease. As fulling caused the cloth to shrink it was then removed and stretched until the desired thickness was achieved. Cloth became England’s main source of wealth in the medieval period so there would have been a clear incentive to take on this work. Some documents refer to fulling mills in Compton Bassett in the early to mid 1700s but it is unlikely they continued for much longer. Small mills generally fell out of use, as larger storage, greater power and mechanisation were needed. The practice of the mill soke had been replaced by this time and millers bought grain direct from farms; the age of factory-scale industrialisation had arrived.

2015 Geophysics Report

A Geophysical survey was commissioned in 2015 ahead of an application to mine sand immediately north-west of the Abberd Brook and up to Freeth farm. The report found an expanse of probable 1st millennium AD settlement south-east of Freeth. Given that early medieval archaeological finds from this area are middle Saxon pottery and mill-grinding stone fragments, this may confirm the site as the missing third estate recorded in the Domesday survey with its adjoining water mill of the same period. The probability that the settlement was abandoned by the 14th century is consistent with the archaeological record and documentary evidence. Despite this, we know that the mill and fishpond remained in use for the two remaining manors and are mentioned later in documents during the 14th and 16th centuries.

Status

In 1999 the mill site was designated as a scheduled monument (1018613):

‘the millpond dams… are well preserved examples of this type of monument. Documentary evidence from the early medieval period shows that the watermill was in use for several hundred years.’

LAURIE WAITE

Sources

Currie, C.K. 1994. Earthworks at Compton Bassett, with a Note on Wiltshire Fishponds. Wiltshire Archaeology and Natural History Society, Volume 87. Hodgen, M.T. 1939. Domesday Water Mills. Antiquity, Volume 13, 51. Watts, M. 2006. Watermills. Princes Risborough: Shire Publications. Somerset Heritage Centre (South West Heritage Trust) Catalogue Ref: DD/WHb Historic England – Scheduled Monuments www.historicengland.org.uk