Potted History

Early Days of Pre-Compton and Environs

The origins of Compton Bassett and its surrounding region stretch back 10,000 years, following the end of the last ice age. As the climate became warmer modern humans began to move into the region. The earliest finds of human activity are flint tools from the Mesolithic period (c.8,000–4,000 BC), indicating post-glacial activity of people hunting and gathering across the region. It was a largely nomadic existence based on the movement of grazing animals and fruit gathering. The occurrence of flint for tool-making in chalklands such as ours made this a resource-rich place in which to be, so the downs immediately south and east became a hotbed of activity as time went on. Unlike other parts of Britain, the landscape of the Wiltshire Downs was dominated by open grassland and only punctuated by outcrops of woodland. Into the Neolithic (c.4,000–2,500 BC), the practice of cultivation and animal husbandry began to take hold and there was a move towards a more sedentary life, as the idea of land division and constructing earthworks and monuments was initiated (eg West Kennet Long Barrow, Windmill Hill, Avebury, Silbury Hill). Windmill Hill, 2½ miles east, is the largest and one of the oldest known examples of a causewayed enclosure (initial phase 3,800 BC), which is an earthwork made up of concentric rings of ditches with frequent breaks in them, or causeways. Its purpose seems to have been as a meeting place for large gatherings of people; numerous cattle and sheep bones found excavated from the ditch fill suggest that it could have been an important place for ceremonial meetings or feasting. A settlement in the Compton Bassett area possibly existed in one form or another from about this period.

Early Bronze Age pottery and worked flint were discovered from test pits dug near Compton Farm in a research project carried out in 1994; this offered the first clear indication of occupation. Other evidence through the Bronze Age (c.2,500–800 BC) comes from the circular burial mounds that pepper the landscape, of which we have six in the parish. The nearest is in Mount Wood and is a fine specimen at over 3 metres high and around 15 metres in diameter; it is so high and conical shaped, that it has been suggested it could conceivably be a later, and rare, Romano-British example.

There is also evidence of Late Bronze Age (c.1,000 BC) activity on the top of Cherhill Down when the first digging of banks and ditches to enclose a 6-hectare site was carried out. Some 500 years later, the enclosure was developed further, extending the earlier work to 9 hectares and creating more elaborate ramparts along the boundary, as well as many internal features of pits and probably roundhouses. Today, we know this site as Oldbury Castle Hillfort. It is the nearest Iron Age (800 BC – AD 100) earthwork to the village, that can be seen today. Roman occupation left traces within the parish, such as pottery fragments in the scarp face at Roach Wood and a probable Romano-British pottery kiln near Manor Farm. The remains of an early medieval watermill and fishponds lie about 500 metres south-east of Freeth farm and the mill is mentioned in the Domesday Survey (AD 1086). The original mill was most likely used for grinding corn and was converted to a fulling mill probably between the 14th and 16th centuries.

The Three Domesday Estates

The early communes that would evolve and later become Compton Bassett appear to have developed from three spring-line settlements. The first originated at the mouth of a coombe where the church and present main house lie. A second settlement with the buildings of Compton Cumberwell manor stood at the mouth of another coombe half a mile north-east. A third estate recorded in Domesday looks to have merged with Compton Bassett manor early in the 13th century and may have existed close to the Abberd brook, between Manor Farm and Freeth Farm. Many villages described in Domesday Book existed in the 5th and 6th centuries AD but there is no documentary evidence for Compton then. What we do have are archaeological finds that show that people were here, living and working.

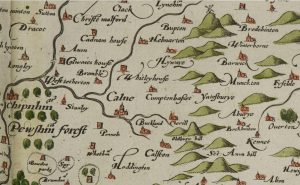

The single-street village of today was almost certainly not connected until the medieval period. Lynchets, or terracing created by plough lines along a hillside, appear to underlie the road from the west end of the village near the war memorial, along towards Compton Farm. This indicates that the two ends formed separate settlements, Cumberwell on the eastern side and Compton to the west. An old hollow way, now referred to as Hooper’s Lane was the main route from Cumberwell up to Compton Hill and the down pasture; this then led to Nolands, Yatesbury and beyond to Marlborough. Compton existed as part of the Calne Hundred and its route connection lay in that direction. Freeth is the possible third settlement at Domesday because of its proximity and access to the watermill. Land near Freeth Farm was surveyed in 2015 by geophysics, revealing traces of former tracks, field systems and likely occupation in the subsoil.

In the Domesday Book Contone (possibly King’s Land), is given as the Latinised version of the origin of modern Compton Bassett. Following the Norman invasion, the Domesday Survey recorded Compton [Bassett] as three estates totalling 17½ hides, an assessment chiefly based on land quality rather than actual area and used for taxation. It is estimated to have had sufficient arable land for 12 plough teams, together with 68 acres of meadow, 30 acres of pasture and 30 acres of woodland. The population was said to be 53 households (possibly around 190 to 220 people), putting it in the top 20% of settlements recorded in Domesday. Consequently, Compton was obliged to provide three fully armed soldiers to serve the king. Domesday records the names of a tenant-in-chief, or overlord, who ‘held’ the land on behalf of the king.

You can read more about the three Domesday estates by following this link.

Late and Post-Medieval Estates and Farms

A more recent estate is recorded within the northern area of the present village, held by John Blake in the late 15th century. The main house for Blake’s estate is not known but it is likely to have developed into Manor Farm, which was built in 1691. At that time the Maundrell family were in possession and continued for several generations until the early 19th century. By 1831 it was acquired by George Walker-Heneage.

In 1719 Michael Smith bought two dwellings and 120 acres of land on the northern outskirts of the village. The old houses were later demolished and his son, Michael Jnr, set about building a new house for which the foundation stone was laid in 1737. This house would later be called Dugdale’s. Smith was married to Margaret Sharpe, a young widow and heiress who hailed from Compton Bassett herself. It passed through the Smith family for two generations and then, in 1780, went to a niece and her husband, Richard Dugdale. When Richard’s grandson sold it in 1855 to the Walker-Heneage family, it had increased in size to 350 acres. The main house with gardens, outbuildings and adjacent fields amounted to 42 acres. The other major part was Lower End Farm which totalled 273 acres.

Streete Farm, the first phase of which is around 1700, and Austin’s Farm opposite (originally an early 16th-century hall) are close to each other along with Manor Farm. This group was referred to as Silver Street in the 1773 edition of Andrews and Dury’s map. Silver Street is a commonplace name for which there are several possible definitions; a more likely one derives from a corruption of the Latin silva, which means wood. Because of the Latin connection, it has often been found to be associated with Roman origins. It is also conceivable that it is a corruption of Selewyn’s Street, recorded in the 13th century.

The Advent of the Walker Heneages

John Walker of Lyneham, who held an estate there and was also lord of Compton Cumberwell manor, bought Compton Bassett House in 1758 and his son John Jnr bought the rest of the Compton estate in 1768. This merged the two manors into one and another ten years on the younger John took on the additional surname Heneage through his grandmother. He was thus the first of four Walker-Heneages who would control and expand the estate of Compton Bassett by purchases and through Acts of Inclosure. But he died in 1806 without issue, so the estate passed on to his great-nephew George Heneage Wyld who was then encouraged to take the Heneage surname to ensure all of its privileges, becoming George Heneage Walker Heneage. This second Walker-Heneage initiated major changes to the village.

The Village post-1950s

It was not until 1953 that mains electricity became widely available in Compton Bassett and mains water would not be installed until the 1960s. Of the seven separate farms: Freeth, Home, White’s, Compton, Manor, Dugdales and Lower End, all except Freeth were dairies. But before the century was out, this had whittled down to just one, at Manor farm. The village school closed in March 1964 as the number of children attending had been steadily declining since the war.

Sources

Blackford, J.H. 1941. The Manor and Village of Cherhill. Private Publication.

Crowley, D.A. (ed.) 2002. A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 17. London: Victoria County History.

Reynolds, A.J. 1994. Compton Bassett and Yatesbury, North Wiltshire: settlement morphology and locational change. Papers from Institute of Archaeology 5.

Stephen, L. and Lee, S. (eds). 1885–1900. Dictionary of National Biography. Volumes I–63. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Open Domesday. Maps and site by Anna Powell-Smith. opendomesday.org

Somerset Heritage Centre (South West Heritage Trust) Ref: DD/WHb

The National Archives. nationalarchives.gov.uk