The Three Domesday Compton Estates

1. Compton Estate

Comprising an estate of 5½ hides, in 1066 Compton manor existed in the position of the present house and church, and was controlled by a Saxon thegn named Leofnoth (Leuenot) on behalf of the king. The name Compton simply means a farmstead or village in a valley, derived from Old English cumb + tūn.

By 1086 Pagen (Payn) of Compton is stated as being the under-tenant to the overlord, a Hunfridus de Insula, or Humphrey de L’Isle (1032–1091). Born in France, de L’Isle almost certainly came over in support of, and benefitted from, the Norman Conquest (he held no lands here before this time yet succeeded in having 27 estates afterwards).

His great-granddaughter Adeliza de Dunstanville (1118–1186) was granted the estate in 1163–4 and was by then married to a Thomas Basset (c.1125–c.1182) in c.1154. This is the first time a Basset (with one ’t’) appears in records connected to Compton Bassett, which was now part of the barony of Castle Combe. The

Bassets were settlers from Normandy at around the time of the invasion; their name is derived from Norman for a person of small stature. Thomas belonged to the second generation of Bassets to enter royal service, to Henry II in 1163; he was a baron of the exchequer, a judge in the south and west, and sheriff of Oxfordshire. He granted his younger son Alan Basset (c.1160–1232) Compton Bassett manor between 1180 and 1182. Alan served as royal advisor to Richard I, and King John and later continued his close association to the monarchy with Henry III. At this time, Alan’s older brother Gilbert Basset (1154–1205) gave Compton Bassett church, together with four other churches, dwellings and land to help fund an Augustinian priory at Bicester.

By now the village was known as Cumptone Basset, documented as such in 1228. Alan’s son Gilbert (c.1190–1241) inherited the estate in 1232 and had already been in service to the king for some years. He endured a testy relationship with King Henry III, to the extent that his lands were forfeited when he and his brother Philip joined in rebellion against the king. However, by 1234 the king gave Gilbert the kiss of peace and his estate was restored. Gilbert married Isabel de Ferrers, the owner of a second estate in Compton Bassett and when he died falling from his horse in 1241, she was assigned his manor of Compton Bassett as dower. She remarried the next year to Reginald de Mohun, who held the two manors until their reversion to Gilbert Basset’s brother Fulk (c.1190–1259) and thence, on Fulk’s death, to a third brother, Sir Philip Basset (c.1185–1271). After he had been reconciled with the king in 1231, Philip embarked on a crusade in 1240 and thereafter remained in active royal service. He served as Justiciar of England and assisted with the administration of the country during Henry III’s absence in France in 1259/60 and again in 1262. By the time of his death in 1271, he held lands in much of southern England. When Philip died without male issue, the Basset family connection dropped out of the village. His daughter Aliva inherited and after she died in 1280 it passed to her son Hugh Despenser, who suffered a major fall in royal favour. His estates were forfeited and he was exiled. His properties were plundered by the Earl of Hereford with furniture, arms and roof lead stolen from the manor house and parks and fishponds were destroyed. Furthermore, the tenants were pillaged and rifled and Compton Bassett village was burnt. The damage inflicted on the village was put at more than £30,000.

Despenser managed to regain his estates and status from Edward II by 1326 but, in another calamitous turn of events, Edward was captured and murdered, while Despenser was handed over to his enemies and beheaded.

The next three hundred years saw a succession of owners interspersed with the Crown holding the estate at various junctures. In the later 14th century there were estimated to be 17 yardlanders (peasants who farmed smaller portions of land, each up to 30 acres) and 16 other customary tenants on Compton Bassett manor. For a while, the estate was held by Queen Katherine Parr, the sixth wife and widow of Henry VIII, until her death in 1552. Compton Bassett manor was then sold to Sir John Mervyn for £952.

Another example of the Crown taking possession of the estate came when Mervyn Tuchet, 2nd Earl of Castlehaven was executed in 1631 for contriving, and assisting in, the rape of his wife, and committing sodomy with his manservants. With his death, his English estates including Compton Bassett were forfeited to the Crown for two years before being restored to Tuchet’s son James. The 3rd earl was not without troubles either: in 1641, amid ongoing financial difficulties, he settled the Compton Bassett estate on his wife, only to see it sequestrated anyway and sold in 1652. Yet this was not to be the end of Tuchet’s connection to Compton Bassett, as the estate was bought by the Thynne family (they of Longleat House) and it was restored to Tuchet in 1657. Tuchet sold Compton Bassett manor to Sir John Weld for £5,000 in 1663 and in the next 11 years before his death he completely redeveloped the house and it then passed to his son William, who promptly left Wiltshire after inheriting a rich portfolio of property elsewhere. His son Humphrey sold up in 1700 to Sir Charles Hedges, whose grandson William dispensed with it to William Northey (1715). In 1758 Northey’s son, also William, divided the manor, selling the house, park gardens and shrubbery, apparently for £4,000, to John Walker of Lyneham (1699–1758), who had earlier inherited Compton Cumberwell from his brother Heneage Walker of Hadley.

John’s son, also John Walker [Heneage] (1730–1806), inherited Compton Bassett house the same year his father had bought it and succeeded in buying the rest of the estate of Compton Bassett from Northey in 1768. He married Arabella Cope in 1763 and, through his grandmother’s lineage (and public petition to the Crown) eventually took on the additional name of Heneage in 1777; this significant name was saved and with it, the family arms and crest. There were no children from this marriage and both of John’s brothers had also died without issue. In 1818, on the death of his wife Arabella, the estate passed to his great-nephew George Heneage Wyld. It became necessary, for the second time in 50 years, to procure a special Licence from the Crown to save the Heneage name; this time changing to Walker-Heneage. It was managed through John Walker Heneage’s elder sister, whose daughter married Reverend John Wyld. He arranged it on behalf of his son George Heneage Wyld (1799–1875), so that the somewhat curious name of George Heneage Walker-Heneage was taken thereafter.

During George Walker-Heneage’s time at Compton Bassett, the village was transformed. The merged manors of the family owned 1,813 acres in the parish by 1838 and the village population of 538 was at its peak. A programme of house building was initiated for employees of the estate which began around the 1840s and continued for around 30 years. Over 30 dwellings were built in an architecturally similar style comprising stone mullioned windows set in a chalk and brick construction with gables and dormers. However, no two houses are identical, featuring nuances in their design or orientation that maintain uniqueness. Chalkstone has been quarried from several sources from the escarpment south of the village road since the 17th century and one quarry was still operating in the 1920s. Tradesmen working for the estate, including carpenters, masons, plumbers, glaziers and blacksmiths all had workshops in a yard at the rear of the Estate House. A village inn, The White Horse, was established in the early 1850s and ran as a public house; a shop with a bakery was added soon afterwards. A new school was built in 1854 and next door a house for the school teacher was added around 1860. In 1868 almshouses for retired estate workers were constructed in a terraced row of six units.

When George Walker-Heneage died in 1875, his son Clement (1831–1901) succeeded. He was the last squire to be born and die in Compton Bassett. Squire Heneage, as he was known to villagers, had retired from the army in 1868, much decorated from 17 years of eventful service. He took over the running of the Compton Basset and Cherhill estates (now 4,600 acres) together with the Lyneham estate of 2,016 acres. Clement died in 1901 and his eldest son Godfrey (1868–1930) inherited. Marrying in 1902, he decided to move his country seat to Coker Court in Somerset, which his wife had inherited. Godfrey and family divided time between their house in London and Coker Court but continued to be involved with the Wiltshire estates, letting out Compton Bassett House for the next 16 years until 1918 when the Compton Bassett and Cherhill estates were put up for sale.

The Co-operative Wholesale Society bought the estates in 1919 and farmed them for ten years. However, operating losses mounted quickly and a protracted employee dispute over union membership led to a decision to sell up. They were advertised for sale in March 1929 and sold to Edward Harding in November; vacant possession was obtained on 25th March 1930. Harding, who lived at West Foscote House in Grittleton, already had an agreement to sell the main house and 777 acres to Captain Guy and Lady Violet Benson for £23,000. Harding held on to Freeth Farm but resold most of the rest of the Compton Bassett estate to A.H. Bond and T. J. Wilson who sold the land in lots soon afterwards. Other portions, including Nolands, High Penn, White’s, Dugdale’s and Breach Farms, various properties in Cherhill and Compton Bassett were resold prior to an auction, held for the remaining lots on 8th April 1930. William Fielding-Johnson bought Manor farm together with Austin’s, Streete, and Dugdale’s farms.

With Guy Benson at one end of the village and William Fielding-Johnson at the other, for a few decades it seemed as if the lords of the manor had returned to Compton Bassett. A new village hall, a war memorial and land provided for social housing, all were made possible through one or both of Benson and Fielding-Johnson through to the 1950s. But Benson sold up in 1948 and Noel Fielding-Johnson sold in 1963 (her husband William had died in 1953).

2. Compton Cumberwell Estate

Standing at the mouth of a coombe, along which runs the track commonly referred to as Hooper’s Lane, was Compton Cumberwell manor (also Comberwell, Comerwell). This second estate also comprised 6 hides. Andrews & Drury’s map of 1773 places the name ‘Compton Comerwell or Comberwell’ across the middle area of the present village, roughly from White’s farm to Compton Hill. Cumberwell is probably derived from cumb, Old English for a short valley, ‘by a stream or spring’.

This was held by Thurkil (or Turchil) de Arden (c.1040–1100) and, unusually for an Anglo Saxon, was still in his possession in 1086. At about this time two water mills were shared equally between those holding the three estates at Compton Bassett in 1086 and could well have been the two mills known to belong to the lord of Compton Bassett manor in 1228. In the late 1100s an exchange of lands took place between Alan Basset and Hugh de Cumberwell, the lords of both manors.

Late in the 12th century or early 13th century William of Cumberwell held the manor. In 1222, it was held by his son Hugh; in 1242–3 Hugh’s son Philip de Cumerwell; and in 1289 by Philip’s son Sir John. In the 13th century Compton Cumberwell manor consisted of demesne (estate) and customary holdings. The overlordship of Compton Cumberwell had become part of the barony of Castle Combe, as Walter de Dunstanville was overlord in 1242–3.

Compton Cumberwell is frequently confused with another Cumberwell (Cumbrewelle), a manor near Bradford on Avon. This is not helped by the fact that, after the Norman Conquest, Humphrey De L’Isle was the overlord of both estates.

The Cumberwell family dropped out by 1327, when a Roger de Berlegh became the holder, followed by his son, Roger Junior. Fishponds are recorded in 1342, belonging to the lord of Compton Comberwell and are described as likely to have been on the clay in Compton Bassett (probably in joint ownership with Compton Bassett manor).

Meetings of a court for Compton Cumberwell manor are recorded for 10 years between 1405 and 1444 and for 11 years between 1548 and 1571. Although most business was tenurial, the homage presented defaulters and those who neglected to repair buildings or scour ditches.

Between 1405 and 1530 it was held by the Blount family or their married relations. One of these, John Hussey, sold the manor to Sir William Button and from then on it passed in direct line for five generations. In the later 16th century four copyholders (tenure of parcels of land) of Compton Cumberwell manor held between them 39 acres of arable, 7 acres in closes of meadow and pasture, and grazing rights for 9 cattle, 4 horses, and 80 sheep. Land holdings for the manors were generally increasing from around this time through enclosure, the controversial removal of common land into private ownership.

In 1660 the estate passed from another Sir William to his brother and, through his wife Eleanor, to a second brother Sir John Button. At the start of the 18th century Compton Cumberwell manor land was still in four holdings. When Button died in 1712, there being no direct line, grandnephew Heneage Walker inherited and when he died in 1758, his brother John Walker acquired Compton Cumberwell. In the same year he bought Compton Bassett house with the parkland and ten years later his son John bought the rest of Compton Bassett estate and merged the two manors.

The manor of Compton Comberwell was still referred to as such on 25 July 1807 when a newspaper notice was published from Compton House to warn people from trespassing and poaching on their lands (which included Compton Basset, Cherrill, Lyneham and Preston).

3. The Third Domesday Settlement

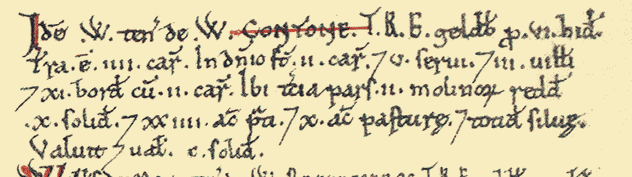

Fragment from the Wiltshire page in Domesday Book detailing a third estate in Contone (Compton).

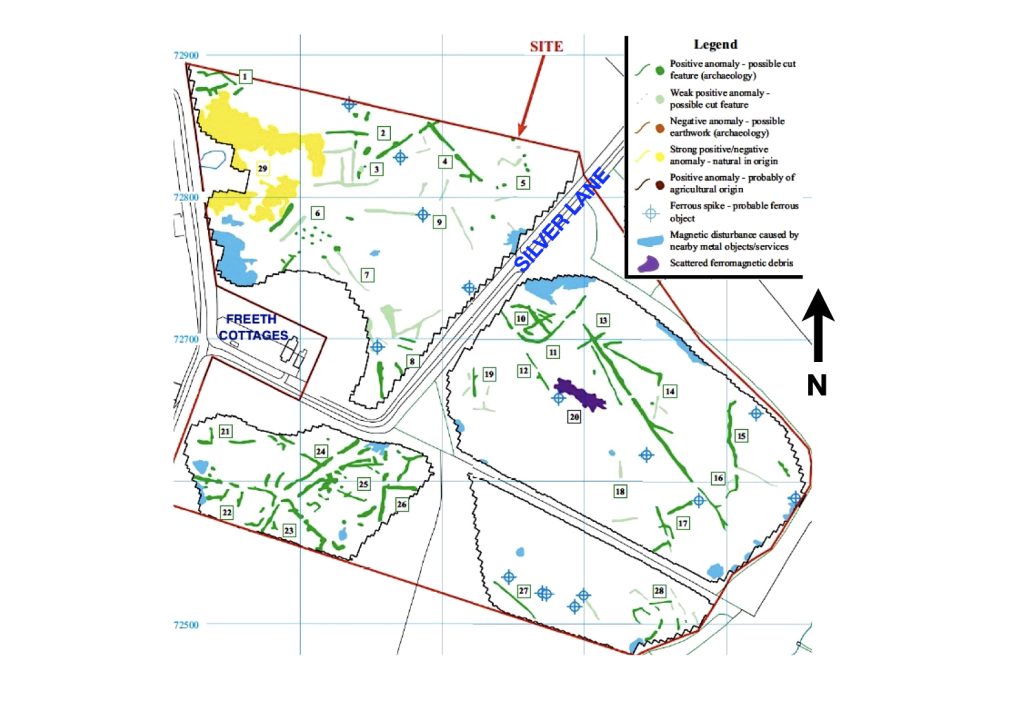

The possibility of a former early settlement near Freeth Farm in Compton Bassett has been known for a few years now, especially since a geophysical survey was carried out in 2015 to evaluate a proposed sand quarry site for any archaeology. It revealed a complex arrangement of buried features, which occasionally show up as crop marks in times of dry weather. Initial assessments indicate that these underground features are the surviving footprints of enclosures, connecting tracks and droveways. In short, an abandoned settlement that could have its roots in the Iron Age.

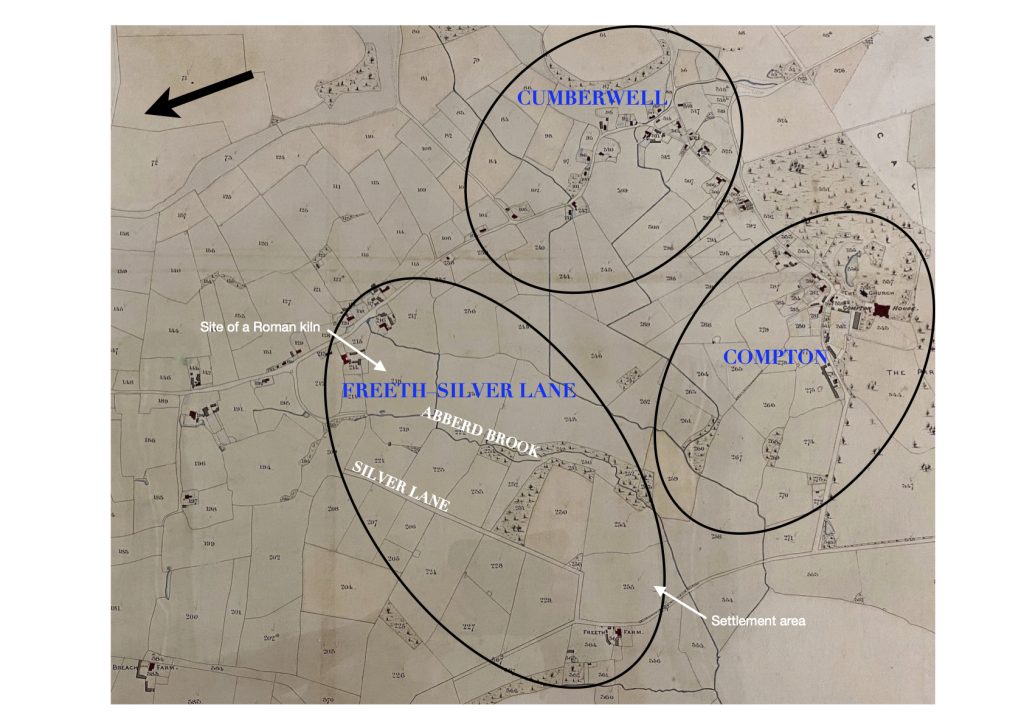

1839 Tithe map annotated to show the Compton and Cumberwell estates and possible location for the third settlement described in the Domesday survey.

So, what makes this the deserted village? Evidence has been steadily accumulating and is compelling.

Three separate estates existed at the time of the Domesday survey within the current parish area. Compton was concentrated near the church and a second estate called Cumberwell was situated to the east, at the head of a coombe in the vicinity of the present Compton Farm.

However, the third estate’s whereabouts, which contained 19 householders in 1086, have been something of a mystery even though all three had an equal share in the mill operation along Abberd Brook then and are well documented. Part of the reason for its loss is that the third settlement merged with Cumptone Basset around the mid 13th century, leaving two estates until Compton Cumberwell merged with Compton Bassett around 1768.

According to Domesday, the third estate in Compton [Bassett] was assessed to be 6 hides, perhaps 700 acres. It was held by William de Aldrie, cousin and steward to William d’Eu. The two, with others, conspired to murder William II but after a long campaign of some years, they were eventually captured in 1095. William, Count d’Eu was challenged to trial by combat at Salisbury but was defeated; thereupon he was blinded and castrated, this being the traditional punishment. Cousin William de Aldrie was sentenced to death, carried out by hanging.

The estate passed to the Earl of Pembroke and subsequently to his granddaughter Isabel de Ferrers, the wife of Gilbert Basset. With Gilbert’s death and Isabel remarrying, the estate was briefly held by her second husband Reginald de Mohun in 1242–3. Thereafter it drops out of the record and seems to have been merged with Compton Bassett manor.

A scrutiny of the archaeological record shows that a considerable amount of Iron Age to early medieval material has been recovered from the fields between Freeth Farm and the Abberd Brook. Fragments of quern-stone (mill grinding stones) have been picked up and pottery of middle Saxon date (8th-9th centuries AD). The results from the geophysical survey showed that all the fields in the quarry site contain a large number of magnetic anomalies, or buried features, such as ditches and pits. Their layout suggests housing and farming enclosures. Even though the structures would have been timber-built, buried evidence will survive in the form of post holes and cut features for ditches that should be recognised during excavation. It’s more than possible that some interesting and datable artefacts will turn up if and when a pre-quarrying, archaeological excavation is carried out.

The Abberd Brook was essential for a reliable source of water and the area around was a well-wooded resource. The name given for the track that leads into the settlement is Silver Lane; Silva is Latin for a dense collection of trees. A short distance along Silver Lane from Freeth takes you to a site of a Roman kiln, a little south-west of Manor farmhouse, where a considerable amount of Roman pottery sherds and evidence of burning was discovered there during pipe-laying in 1986. Two Roman coins were found nearby during the 1970s.

After it was absorbed by the Compton estate, the settlement was abandoned most likely during the latter half of the 13th century, consistent with the archaeological record and documentary evidence. All this will be evaluated during a major archaeological excavation which has to take place before any quarrying operations can start, after which a great deal more will be known about the history of this lost settlement.

The eastern side of the geophysical survey adjoins the Abberd Brook and the remains of a Saxon watermill and fishponds. Despite the loss of settlement, the mill and fishpond remained in use for the two surviving manors and are mentioned in 1342, in a description of a ‘hamme’ of meadow lying by the lord’s fishpond. And in 1529, the miller was brought to the court of Compton Bassett manor, accused of overcharging.

2015 Geophysics survey. A large number of buried features such as pits, ditches and enclosures were revealed. In the south-western field (containing numbers 21-26), likely paths, droveways and buried structures indicate a possible settlement area.

LAURIE WAITE

Sources

Blackford, J.H. 1941. The Manor and Village of Cherhill. Private Publication.

Crowley, D.A. (ed.) 2002. A History of the County of Wiltshire: Volume 17. London: Victoria County History.

Reynolds, A.J. 1994. Compton Bassett and Yatesbury, North Wiltshire: settlement morphology and locational change. Papers from Institute of Archaeology 5.

Stephen, L. and Lee, S. (eds). 1885–1900. Dictionary of National Biography. Volumes I–63. London: Smith, Elder & Co.

Open Domesday. Maps and site by Anna Powell-Smith. opendomesday.org

Somerset Heritage Centre (South West Heritage Trust) Ref: DD/WHb

The National Archives. nationalarchives.gov.uk