The Co-op Years in Compton Bassett

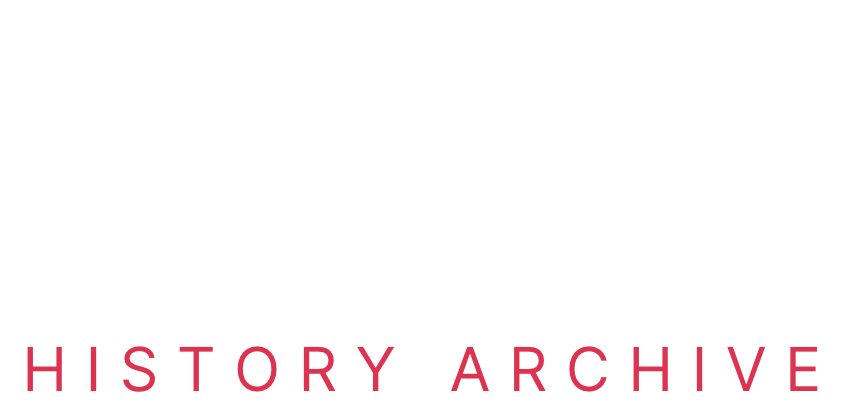

The Co-operative Wholesale Society Ltd (CWS) agreed to purchase Compton Bassett estate and neighbouring parish lands, totalling 4,607 acres, at Christmas 1918 after it had been put up for sale by Godfrey Walker-Heneage, whose family had first bought Compton House and associated land in 1758 and had steadily built up the estate ever since. CWS had already taken possession of Manor Farm, Cherhill and Home Farm, Compton Bassett three months earlier, and the final deal amounted to £108,000 (£6m in 2023). Another 151 acres were added in portions over the next few years.

By the end of the First World War, the cooperative movement had become a leader for social change when it began reducing the maximum working week to 48 hours, increasing wages and improving working conditions, while at the same stroke providing paid annual leave, paid sick leave, and pensions. The Co-op dividend (“divi”), had now become a British institution with pay-outs provided twice a year to members, who numbered over 3 million in England and Wales by 1920. The movement had grown rapidly since the early 1900s, in tandem with a burgeoning interest in socialist politics. This influence rose despite, or perhaps because of, the economic and political crises of the inter-war years. A marked divide grew between the likes of major capitalists and conservatives such as outspoken critics, Lord Rothermere (Daily Mail owner) and Lord Beaverbrook (Daily Express owner), and a rapidly growing socialist movement that became dominated by the British Labour Party, which won its first General Election in 1923.

As early as March 1920 questions were being asked about Co-operative Societies’ tax liabilities, as they enjoyed exemptions from income tax. A Commission on Income Tax had recently resolved in favour of making them liable but as a newspaper correspondent wrote, “The Co-operative Wholesale Society purchased the Compton Bassett estate; an old mansion of 40 bedrooms, and extensive park and pleasure gardens, several farms and practically the whole of the cottages in the village. It is generally understood the late squire used to pay £1,000 a year income-tax on it, but this society pays nothing but can give £1,300 for a house.” The Daily Express portrayed the Co-operative movement as an unpatriotic, socialist organisation. On the other side of the argument, ‘The Great Tax Ramp’, as it became known, was regarded as a direct challenge to democracy. The argument raged on for years inside and outside parliament with legislation eventually coming in the 1930s. The Co-op had lost this battle but the financial impact on them was limited, as societies easily avoided the new taxation and the movement continued to expand.

Back in Compton Bassett, the farms of the estate were taken over gradually, and it was not until late in 1925 that the last farmer, Harry Bodman, left the village. Bodman lived at Dugdales Farm but also ran Streete and Austin’s farms. The estate was now unified under central control, and the CWS began to address the question of union membership.

CWS had always encouraged its employees to become members of an affiliated trade union and, by the mid-1920s there was much passionate debate about whether membership should be made compulsory. Indeed, for new employees this was already the case. Many members supported the ideal, yet were troubled; as one delegate summed it up, “How can you have co-operation by compulsory measures?” Compton Bassett villager Jack Fell’s memoirs recall how this came to have serious consequences for the Compton Bassett workers.

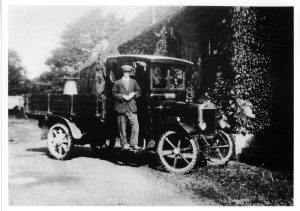

In 1927 employees were called to a meeting at Cherhill village hall where a union leader named Mr Walker told them about the benefits; Charles Darch, a CWS director was also present. For the villagers, Harry Stevens and Steven Clifford were there to represent them. When the trade union official got to his feet to address the workers, this was their pre-arranged cue to all walk out of the hall. Then, as Charles Darch was about to speak everyone trooped back inside. A workman called out and asked about the union benefits, to which Darch replied, “Ah well my man, Mr Walker was here to tell you and you would not give him a hearing. I’ve not come down here, ladies and gentlemen, to urge you either one way or the other but I’ve come to tell you the real facts that the Co-operative Society have no alternative whatsoever to lay before you, and it’s up to you to join the union, and we will give you one month to decide. Remember, you’re only a mere handful to our vast organisation.”

In response, the 169 farm workers gathered in Compton Bassett school room in May 1927 and passed a resolution that stated they “emphatically protest…that we should become members of a Trade or Workers’ Union… The whole of the employees on this estate have definitely decided that we will not become members of any union affiliated to the Trade Union Council movement.” Newspaper reports raised the question that if CWS workers refused to join a union, would they then be dismissed?

The answer came swiftly, the employees received notice from CWS that, unless they joined a union affiliated with the Trade Union Congress, they would indeed be dismissed from their service. The matter was raised in Parliament on 20 June 1927 when local MP Captain (later Colonel) Victor Cazalet (1896–1943) sought to highlight the issue in a debate about public companies making it a condition of employment. “Coercion and compulsion of this kind are, surely, contrary to all the principles of co-operation”, he said. “They [the 169 Compton Bassett agricultural workers] do, however, very strongly object to being dictated to, and to being ordered to join a particular union, because, they disapprove both of its politics and of the policy which has been pursued in the past by that particular union.” The workers were not, in the event, dismissed but the fate of the estate was soon to be resolved by other means.

Amid the general economic crisis in the UK during the 1920s, huge losses started to be reported from the running of the Compton Bassett estate; in 1927 alone it was £21,546 (£1.7m in 2023). Another estate at Down Ampney also made a loss. In 1928, at a meeting of divisional shareholders in London, it was disclosed that losses totalling £454,000 (£35m in 2023) had now accumulated for the two estates and only one of their farms across the country, in Northumberland, showed any profit.

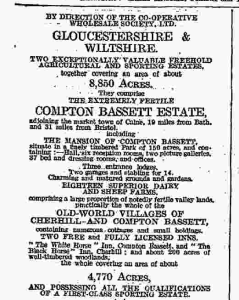

It was announced on the 8th September 1928 that the estates of Compton Bassett and Cherhill (now 4,758 acres) would be disposed of, along with the estate at Down Ampney. These were advertised for sale in March 1929 with Compton Bassett being sold to a syndicate headed by Edward Harding in November; vacant possession was obtained on 25th March 1930 and two days later, the main house, farm cottages and estate lands totalling 777 acres, were sold on to Guy Benson for £23,000. The Co-op reversed its decision to sell Down Ampney and, as of 2021, is still in their ownership.

The sale brought to an end ten years of CWS connection to Compton Bassett that was not without tribulation. By April 1930 the whole estate stock had gone; not a cow, horse or sheep was left in the village. Despite CWS’s loss-making across their estates during this period, Compton Bassett was the only one they abandoned, and the union dispute played no small part in this decision.

LAURIE WAITE

Sources

Fell, J. 2010. Memoirs of a Countryman. Private publication.

Gurney, P. 2015. ’The Curse of the Co-ops’: Co-operation, the Mass Press and the Market in Interwar Britain. Research Pepository: University of Essex.

Redfern, P. 1938. The New History of the C.W.S. London: J. M. Dent & Sons Ltd.

The People’s Year Book. 1920. Manchester: Co-operative Wholesale Society.

The People’s Year Book. 1939. Manchester: Co-operative Wholesale Society.

UK Parliament. Hansard Volume 207: debated on Monday 20 June 1927.