A mere two decades after the war to end all wars, the grotesque mayhem of human suffering struck once more. An even deadlier conflict claimed the lives of around 80 million people across the world. The villagers of Compton Bassett answered the call to defend their country against an existential threat; five more paid the ultimate price.

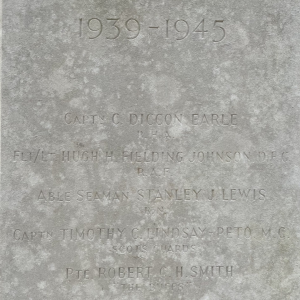

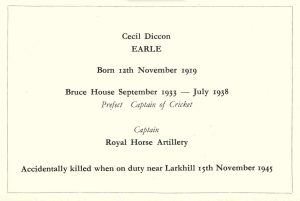

Captain Cecil Diccon Earle 160258

11th Royal Horse Artillery (Honourable Artillery Company)

Born 12 November 1919

Died 15 November 1945

Family lived at Manor Farm, Compton Bassett

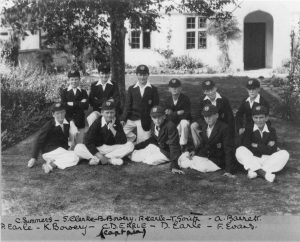

Diccon Earle was born in London to parents Brigadier Eric Greville Earle DSO and Noel Earle (née Downes-Martin). His parents divorced when he was 12, in 1931 and later that year his mother married William Fielding Johnson. Together they moved to Manor Farm in Compton Bassett which Fielding Johnson had just purchased. Diccon was educated at Stowe School in Buckinghamshire from 1933 to 1939. He excelled at sports and was noted as a great all-rounder.

After leaving school, he joined the army and was commissioned as a 2nd Lieutenant at the end of his initial officer training course in December 1940. He was promoted to Lieutenant in May 1942. He attained the rank of Captain in 1944 and the following year completed a post-war gunnery school, passing out with high honours; he was expecting to be posted overseas. He married Elizabeth Anne Sainsbury in 1943 and moved to Weston-Super-Mare where she was a policewoman, the first in the town’s force.

However, tragedy struck six months after VE Day, when 26 year-old Diccon Earle was killed while out on the edge of Salisbury Plain at Larkhill. A gun he was riding on skidded, throwing him off into the path of another gun. He was buried at Weston-Super-Mare Cemetery, Section Z, Grave 533.

Flight Lieutenant Hugh Henry Fielding Johnson DFC 130659

21 Squadron, Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve

Born 24 June 1921

Died 22 February 1945

Lived at Manor Farm, Compton Bassett

Born at Strancliffe, Barrow-Upon-Soar, Leicestershire, this was the family home of the Fielding Johnsons but his parents William Spurrett Fielding Johnson and Gwendolen Edith Whetstone divorced in 1929 and his father married divorcee Noel Earle (née Downes-Martin) in 1931 after she had divorced earlier that year. His mother died in a road accident at Redbourn, near St Albans in 1935 after which Hugh went to live at Compton Bassett with his father and step-mother Noel. He was educated at Marlborough College 1935– 40 and subsequently volunteered for the Royal Air Force Volunteer Reserve, in which he was a Leading Aircraftman in September 1942. He flew 15 sorties flying Mustang aircraft before joining 21 Squadron in March 1944 flying his first mission with them in a De Havilland Mosquito on 26th March along with his navigator Flight Officer Leonard Harbord.

His commendation from senior officers gives some idea of his dedication:

Particulars of meritorious service for which recommended:-

This officer has completed 50 operational sorties in his first tour of operations, in addition to 15 patrols flying Mustang aircraft before he joined this Squadron.

These sorties include five high-level daylight operations, seven flower operations against enemy aerodromes at night, two low-level daylight sorties and thirty-seven night sorties against rail and road transport in France in support of our armies since D-Day.

The low-level sorties include a comparatively deep penetration to Bonneil Matours on July 14th. when a German Barracks was attacked at dusk. On 4th July whilst on a night patrol to La Rochelle one engine was hit by flak. Even though he was at only 1,000 feet and 250 miles from base F/O. Fielding Johnson succeeded in bringing his aircraft back and landing safely at his aerodrome, showing great skill and perseverance.

Since D-Day, he has damaged eight trains and has attacked numerous transport and three convoys on the roads.

On the night of the 28th of August he discovered many trucks in the marshalling yards at Charleville and successfully attacked them. Upon returning to base he then took off again to attack the same target, showing the great enthusiasm and determination which has marked his whole operational tour.

This pilot’s skill and enthusiasm could not be excelled and I have no hesitation in recommending him for the D.F.C.

Remarks by Airfield Commander.

A very fine pilot and a gallant Officer, F/Lt Fielding-Johnson has filled his 65 operations with action damaging to the enemy. He is undeterred by opposition, and I very strongly recommend him for the award of the Distinguished Flying Cross.

Remarks by Air Officer H.Q. No.2 Group.

I strongly endorse this recommendation. I cannot speak too highly of this officer’s courage and devotion to duty. He possesses great determination and fearless courage. He has achieved very great success in his operations and I recommend him very strongly indeed for the award of the D.F.C.

Fielding Johnson was killed during Operation ‘Clarion’, a daylight raid in Germany, taking off at 11:30 hrs on the 22nd February 1945. Their target was one of 200 German communication networks, their being in the Hannover and Bremen area. Targets included “rail stations, barges, docks and bridges”. Operation Clarion opened ground offences Operation Veritable and Grenade. He and his navigator targeted the marshalling yard in Hildesheim during the afternoon and due to good weather and clear sight the marshalling yard was heavily damaged. They were met with ground fire but it is thought that German fighter aircraft pilots claimed the downing of Fielding Johnson’s Mosquito.

Fielding Johnson was killed during Operation ‘Clarion’, a daylight raid in Germany, taking off at 11:30 hrs on the 22nd February 1945. Their target was one of 200 German communication networks, their being in the Hannover and Bremen area. Targets included “rail stations, barges, docks and bridges”. Operation Clarion opened ground offences Operation Veritable and Grenade. He and his navigator targeted the marshalling yard in Hildesheim during the afternoon and due to good weather and clear sight the marshalling yard was heavily damaged. They were met with ground fire but it is thought that German fighter aircraft pilots claimed the downing of Fielding Johnson’s Mosquito.

The cemetery of Ströhen is recorded as the initial burial location, which usually is very close to the place of the actual crash. He was subsequently reburied some 80kms east at Hanover War Cemetery, Seelze, Lower Saxony. Plot 8.K.2. Hugh was 23 years old and unmarried. His step-brother Diccon Earle was also killed later that year.

Able Seaman Stanley John Lewis D/SSX 13581

Royal Navy

Born 27 October 1914

Died 8 June 1940

Family lived at 68 Compton Bassett

Born at 68 Compton Bassett to parents Charles Lewis and Rosa Jane Lewis (née Clifford); his mother died in 1917 and his father worked as a thatcher. Stanley joined the Royal Navy and in 1940 was posted to HMS Glorious; he was lost at sea in the biggest single loss of life for the Royal Navy during the Second World War.

The following text was written by naval historian Philip Weir:

Late in the afternoon of June 8th, 1940, the Royal Navy suffered one of its most devastating defeats of the Second World War. HMS Glorious, one of Britain’s largest and fastest aircraft carriers, was sunk along with her escorting destroyers HMS Ardent and HMS Acasta. The three British warships were taking part in Operation Alphabet, the evacuation of Allied forces from Norway that had been taking place simultaneously with the rather better known and remembered evacuation at Dunkirk.

At 0300, Glorious and her escorts detached from Vice Admiral Lionel Wells’ aircraft carrier squadron, which was covering the evacuation convoys on their journey back to Britain, and headed home. She had been assigned to evacuate ten biplane Gloster Gladiator fighters of the RAF’s 263 Squadron. In a remarkable feat of seamanship and flying, seven Hawker Hurricanes of 46 Squadron also managed to land on her flight deck: something previously thought impossible for high performance monoplanes, unadapted to naval work. At 1545 they were spotted by the German battleships Scharnhorst and Gneisenau. With no aircraft in the air to provide an early warning, and despite a heroic, Victoria Cross- nominated defensive performance by the destroyers, escape proved impossible. By around 1820, the valiant Acasta, last of the British ships still afloat, which had torpedoed Scharnhorst in a last gasp attack, sank, blazing, beneath the waves.

Aboard Scharnhorst a film crew recorded the action and Glorious became perhaps the first major Royal Navy ship whose demise was seen in moving pictures, triumphantly displayed to the world only days later on the newsreel ‘Die Deutsche Wochenschau’.

Some 900 men went into the cold, northern waters that evening and they faced a horrifying ordeal. Despite saluting their gallant foes, the German battleships did not stop to pick up survivors. The British, on the other hand, unaware that the three ships had been lost until the following day, even continued to radio orders to them until the Germans announced the sinkings. Hour after hour men waited in the water and in open rafts as their shipmates slipped away around them. When Norwegian vessels finally found them nearly three days later, only 40 remained alive. The death toll of 1,519 exceeded any of the other great British naval disasters of the war. Among the dead was Glorious’ Captain, Guy D’Oyly- Hughes, a highly decorated submariner whose First World War record was legendary. One of the Royal Navy’s precious few large aircraft carriers had been sunk, along with two destroyers and, with the Battle of Britain in the offing, two RAF fighter squadrons. The Admiralty Board of Enquiry was held within days of the 34 available survivors returning to Britain, its findings then sealed until 2041.

Controversy began almost immediately, with questions first being asked in Parliament on the July 31st, 1940 culminating in a debate on November 7th. Richard Stokes, a noted critic of the government, was prime mover, asking just how and why such an epic disaster could have occurred and who bore responsibility. Inevitably, given wartime exigencies, no answers were forthcoming from the Admiralty. The war moved on and the issue went quiet for some years until in 1946, after further probing from Stokes, a brief official account was released. It described a ship travelling independently due to shortage of fuel on a normally safe route that had simply run out of luck and been caught in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Also steaming home independently, Devonshire was carrying the Norwegian royal family to safety in Britain. Officially, she received only a corrupted message from Glorious and maintained radio silence until the following day, passing it on when its significance became clear. Devonshire’s signal logs did not survive, but changes in course and speed, a main armament drill at the time of the sinking, plus testimony from veterans of her crew to the documentary crew all suggested that Glorious’ message may not have been so corrupted after all. Thus, questions began to be raised over whether the crews of Glorious and her escorts had in some respects been sacrificed to protect Devonshire and the Norwegian royal family. This opened another round of questions in Parliament, most notably from Tam Dayell, and a seven-page official response from the Ministry of Defence entitled H.M.S. Glorious – Points of Controversy, which broadly restated the Admiralty’s original case, particularly over the fuel and radio issues.

Perhaps inevitably, in recent years the controversy that surrounds the loss of the three ships seems to have lost some of its heat, with positions entrenched and the number of veterans dwindling. Yet the three ships and the men who sailed in them are still commemorated in Plymouth each June by GLARAC, the HMS Glorious, Ardent and Acasta Association. Moreover, with seemingly little resolved between the official and other accounts of the sinkings, and public interest in the Second World War remaining high, it seems certain that we have yet to hear the last of this tragic, controversial episode.

The war grave of Stanley Lewis is at the Naval Memorials in the United Kingdom Plymouth Part VI. Panel 38, Column 1.

Captain Timothy Clement Lindsay-Peto 219062

1st Battalion Scots Guards

Born 23 January 1921

Died 24 April 1945

Home address listed as Compton Bassett House in 1941

Tim Peto was born in London to parents Major Ralph Peto and Ruby Lindsay; they were divorced in 1923. Ruby Lindsay was cousin to Violet Manners (daughter of Duke of Rutland) who married Guy Benson, which helps to explain his connection to Compton Bassett; at the time war broke out Tim and his sister were registered as living at Compton Bassett House with the Benson family.

His mother Ruby reverted to her maiden name of Lindsay in 1926 and Tim used Lindsay-Peto from about this time. He was educated at Eton College from 1934– 1939 and the family lived at 23 Connaught Square, London. On leaving Eton Tim joined the Scots Guards and late in 1941 he was promoted from 2nd Lieutenant to War Substantive Lieutenant. By 1943 he was posted to North Africa and was wounded on 29 April. Recovered, and now a full lieutenant, he was sent with British and American forces to establish a beachhead at Anzio, Italy. During this campaign, on 10th February 1944, he was recommended for a gallantry award. On 21st February he is recorded as being injured again.

On the 20th April he received the news that an MC was to be awarded. The citation reads:

In the Carroceto area (south of Rome, near the coast) on the morning of February 10th, Lieut Lindsay-Peto’s company was surrounded after an enemy night attack. The fifty survivors being of no further use to our defence, were ordered to fight their way through to the rest of the Battalion. This involved crossing 500 yards of open ground under direct fire from tanks and machine guns on either flank and breaking through an enemy company that was occupying the station. Lieut Lindsay-Peto led the leading platoon with great dash and gallantry. After 50 yards they surprised a German platoon in a ditch and this officer leapt straight in with his revolver and those of the enemy who were not killed, surrendered. Leaving one man to bring on the prisoners, Lieut Lindsay-Peto led the way up the ditch, surprising and overwhelming two more small parties of the enemy. As they reached the station a German officer jumped up from a dugout and tried to fire his rifle – however it jammed, and Lieut Lindsay-Peto, whose revolver had also jammed, rushed at him and tackled him. While they were struggling on the ground, the platoon Sgt who was some distance away, arrived and finished off the half-strangled German officer with his tommy gun. Lieut Lindsay-Peto then continued the rush through the enemy position and finally joined the Battalion with very few casualties among his platoon. The success of this seemingly impossible operation which was carried out in broad daylight was largely due to the very great dash and bravery of this officer. The speed with which he led his platoon and dealt with every German in their path completely demoralised the enemy, and so the remnants of a company which seemed to face almost certain annihilation were able to rejoin the Battalion at a time when reinforcements were desperately needed.

Granted an immediate MC, signed General H.R. Alexander, Commander in Chief, Allied Central Mediterranean Force.

The award was officially made on 15 June and he was promoted to Captain. He and his battalion moved up country and in Spring 1945 took part in the Battle of the Argenta Gap in northern Italy during the final stages of hard fighting in the Second World War between Allied troops and German panzer forces. The battle was won in a little over a week but Tim was killed in the mopping up afterwards, just five days before the German surrender.

Buried at Argenta Gap War Cemetery, Emilia-Romagna, Italy. Plot Reference I, E, 21. 16 other Commonwealth soldiers are buried there. Captain Tim Lindsay- Peto’s headstone reads:

“He is made one with nature:

There is heard

His voice in all her music”

The site of the cemetery was chosen by the 78th Division for battlefield burials, and it was later enlarged when burials were brought in from the surrounding district. It contains, among others, the graves of many men of the Commandos engaged in the amphibious operations on the shores of the Comacchio lagoon early in April 1945. Argenta Gap War Cemetery contains 625 Commonwealth burials of the Second World War, eight of them unidentified. The cemetery was designed by Louis de Soissons.

Private Robert Charles Henry Smith 14209926

5th Battalion The Buffs, Royal East Kent Regiment

Born 12 July 1922

Died 3 November 1943

Lived at 1 The Breach, Compton Bassett

Born in Compton Bassett, Robert Smith’s parents Henry John and Olive Sarah Smith (née Bullock) lived in the block of four recently built council houses on the north side of the village, close to Breach Farm. Henry was a Compton Bassett villager who worked as a farm labourer; his two elder brothers Jacob and Fred Smith had served in the First World War and both had been injured and invalided out. In 1920 Olive married Henry at her home village in Bletchingdon, Oxfordshire and moved to Compton Bassett where her second child Robert was born two years later. Robert attended the village school and later worked as a builder’s labourer.

5th Battalion The Buffs had been fighting towards the Adriatic coast in central Italy with the Germans preparing to dig in for winter, a defensive position known as the Gustav Line which stretched from the river Garigliano in the west to the Sangro at the east. It was while the Allies were about to attack these positions that Robert was killed on the 3rd November 1943.

Robert Smith is buried at Sangro River War Cemetery, east of Rome and close to the Italian east coast, along with 2,617 other Commonwealth casualties who died fighting the German winter defensive position known as the Gustav Line on the Adriatic sector of the front in November-December 1943. Plot 2.C.13. He was 21 years of age.

The inscription on his headstone reads:

Know this also,

That the Lord hath chosen To Himself

The man that is Godly

LAURIE WAITE

Sources

The National Archives

‘The Great War: Calne District Soldiers’ by Richard Broadhead

Commonwealth War Graves Commission

War Diaries of various regiments.