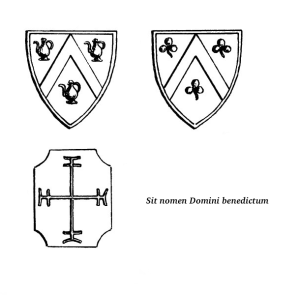

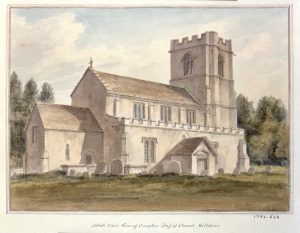

At around one thousand years old, the church of St Swithin in Compton Bassett is comfortably the oldest surviving building in the village and was awarded a Grade 1 Listed Building status in 1960. What we see today is the product of multiple phases of enlargement and restoration from origins in the later Anglo-Saxon period, followed by Norman, Perpendicular (15th century) and Victorian additions. Seven stages of major development have been identified, the last of which occurred in 1866.

1st Millennium Origins

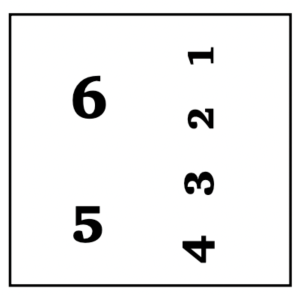

Churches are often found to have been placed deliberately on earlier Christian or pre-Christian ritual sites, initially built and used by the local lord of an estate. In the years after AD 900, small stone-built churches (which later became parish churches) began to appear in greater numbers. There is no mention of a Compton church in Domesday Book, though this is not significant as the survey was not particularly concerned with churches. Certainly, in 1185 the church in Compton had been given to the Augustinian priory of Bicester by the Basset family and in 1228, they were thought to have occupied a house with the church standing nearby.

Three important pieces of evidence discovered during renovation and survey work, point to a possible late 1st millennium AD building on the site of the present-day church. Victorian labourers digging for the construction of a coal cellar revealed a section of substantial foundation wall, apparently unrelated to the present church but conceivably representing the remains of an earlier building. Secondly, Anglo-Saxon period pottery sherds were recovered from a gulley discovered running at roughly right-angles underneath the south aisle, so predating the 13th century addition. And the stripping of plasterwork inside the church in 1999 revealed putative Anglo-Saxon long-and-short work in the limestone quoins within the original north wall exterior face, at its west end (now inside the church after the late 12th century north aisle was added).

Consequently, the earliest phase of the existing church is assessed as being a simple two-celled pre-Norman stone structure consisting of a nave and chancel; it probably belonged to the local Saxon thegn for private worship. The exclusivity of private chapels was as much about projecting status, as it was about religious devotion. Note the likelihood of a south entrance at this time, in direct association with the lord of the manor’s house.

Orientation of the church has not altered since the first phase of construction; at 17 degrees north of east, or east-north-east, this coincides with a local high summer sunrise, although it may be more relevant that the main altar is at the eastern end, facing Jerusalem. Church alignments are not strictly adhered to but generally show an inclination for congregations facing eastward.

Post-Norman Conquest

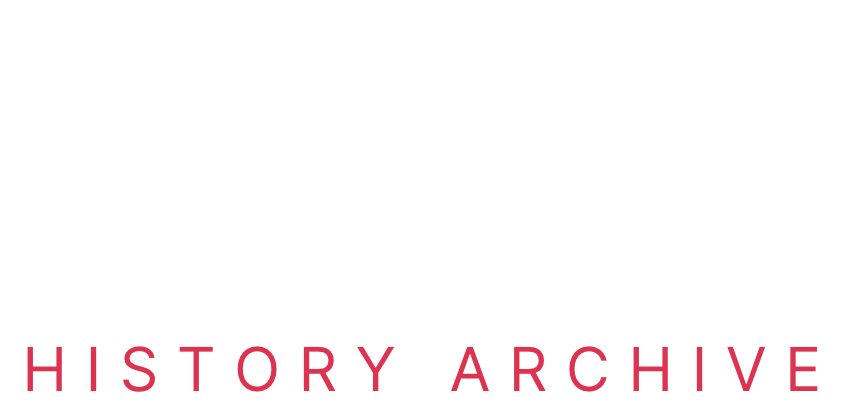

When William I redistributed land to his followers after the successful Conquest of 1066, Compton estate was given to Humphrey de L’Isle, one of many he inherited across Wiltshire. De L’Isle’s great-granddaughter Alice married Thomas Basset in c.1154 and their son Gilbert presented the church to Bicester Priory between 1182 and 1185, which received an income from it until the Dissolution (late 1530s). Despite the Bicester link, the Bishop of Sarum (Salisbury) maintained a right to appoint clergy in Compton, and the church has been in their patronage more or less uninterrupted since 1311.

Episodes of church restoration and additions tend to reflect periods of improved prosperity, helped in no small part by the tithe system, which meant that all parishioners were expected to give a tenth of their agricultural produce to the church each year. An example of better times is in the early 13th century when a south aisle was constructed, probably as a result of the growing population in England which had more than doubled since the Conquest. The new aisle mirrored its late 12th century northern counterpart.

The 15th century witnessed an economy that was recovering following the devastation wreaked by decades of the Black Death and a subsequent Peasant Revolt. The Church had become wealthy and played a dominant part in people’s lives in medieval England. Many churches were redeveloped and upgraded during this period in the latest perpendicular style, and St Swithin’s was no exception. A fifth phase saw major alterations commencing early in the 15th century, when the tower was built. As the oldest bell is dated 1410, this implies a probable date for the tower’s completion. Tree-ring dating of the oak timbers used in the new barrel-vaulted roof, raising the height of the nave, has confirmed that the work was carried out late in the 15th century, featuring a clerestory with three windows on each side.

Later on, a porch was introduced over the door to the church, which is on the northern side. This is an uncommon characteristic and was conceivably the result of a change from an earlier entrance which may have been situated at the south-west end of the building, close to the Lord of the Manor’s house, before the tower was added there in the early 1400s. Three bells hung in the tower in 1553, which were supplemented by the large tenor bell in 1603, and by the 18th century five bells were in existence.

During the second half of the 19th century, as with an estimated 80% of parish churches in England, St Swithin’s received major Victorian refurbishment in 1866 under architect Henry Woodyer. The Norman chancel was completely replaced by the larger aisled structure we see today. The same year saw the installation of an organ by William Sweetland of Bath. The oak pews are 18th century, while other furnishings and fittings are mostly 19th century. The highly decorated hourglass, circa 1650, apparently lasts for half an hour!

Medieval Wall Painting

In 2005 traces of medieval painted decoration were first seen when flakes of limewash overpaint fell away from the north aisle. Conservators uncovered and consolidated the wall painting, over an area of approximately three square metres made up of two sections. The painting is thought to date stylistically to the 14th century and portrays vine scrolling and stencilled motifs.

The Rood Screen

The finely carved stone screen that divides the chancel and nave has attracted much attention as it is likely to have originated from a high-status ecclesiastical building, often suggested to have been Salisbury Cathedral; others have proposed Winchester. However, restoration work at Salisbury between 1789 and 1792, saw several highly detailed Caen stone screens removed from chapels there, of a date and style corresponding to the early 15th century, comparable to the one which is in St Swithin’s. Evidence has not been found for when the screen arrived at the church but there are references for late 17th century or early 18th, in which case Salisbury Cathedral may be discounted as a possible source. Another reference, from 1904, refers to the screen being removed from a side aisle in Winchester Cathedral at an unknown time.

Dedication to St Swithin

Swithin was born in c.800, an Anglo-Saxon who became bishop of Winchester from AD 852 until he died in 863. Over one hundred years later, in 971, he was made patron saint of the restored Winchester Cathedral. The church in Compton Bassett could have been dedicated to St Swithin at any time after this. The settlements of Compton were part of the huge diocese of Winchester, before it was divided in AD 909 and the lands of Berkshire and Wiltshire moved to a newly created bishopric of Ramsbury. This only lasted until 1058, as Ramsbury and with it, Wiltshire were joined to form the diocese of Sarum (Salisbury), where it remains today.

It is feasible that the early connection to Winchester could have influenced the choice of Compton for a popular and native saint, Bishop Swithin. While there is no evidence to confirm the actual time of attachment to Swithin, dedication to churches was normal practice from as early as the 4th century and the early adoption of saints is one reason why post-Conquest saints became patrons of very few parishes. Of the 68 churches of St Swithin, virtually all are considered to have been dedicated to him by the 12th century.

LAURIE WAITE

Sources

Hicks, M.A. 2020. Leavings or Legacies? The Role of Early Medieval Saints in English Church Dedications beyond the Conquest and the Reformation, in The land of the English kin. Leiden: Brill.

Pevsner, N. 1963. The Buildings of England: Wiltshire. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

Reynolds, A. 1993. A Survey of the Parish Church of St Swithun at Compton Bassett, Wiltshire. Wiltshire Archaeological and Natural History Magazine Vol. 86.

Reynolds, A. and Semple, S. 2012. Digging for names: archaeology and place- names in the Avebury region, in Jones, R. and Semple, S. (eds) A Sense of Place in Anglo-Saxon England. Stamford: Shaun Tyas.

Grade 1 Listed Building official entry: click here.